My name is Monica Perusquia-Hernandez, and Assistant Professor at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST). I specialize in Affective Computing, the science of identifying, eliciting, and regulating emotions with technology.

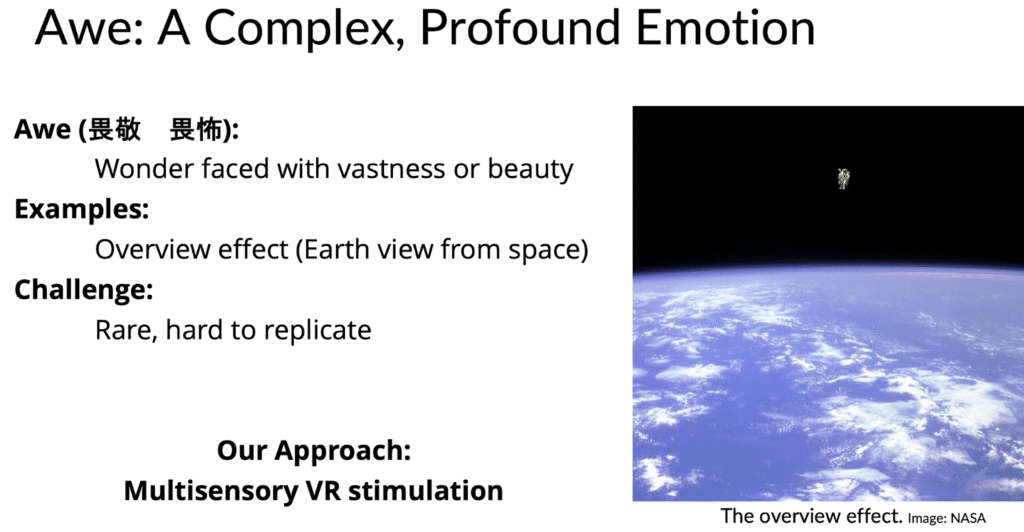

We experience many emotions from birth, and they shape how we perceive ourselves, make decisions, and interact with others. This time, I will introduce the emotion of “awe” (Fig. 1).

What is Awe?

Awe is a self-transcendent emotion characterized by the perception of vastness and the need to accommodate it within one’s existing mental frameworks (Keltner, 2023). It is often triggered by stimuli that challenge our understanding of the world, such as natural landscapes (Joye & Bolderdijk, 2015), architectural structures, or powerful music (Maruskin et al., 2012).

Why is Awe good for well-being?

Profound psychological states, such as the emotion of awe, are often characterized by a modulation of self-perception, specifically a feeling of the “small self” — a diminished sense of personal scale and significance relative to something perceived as vast (Piff et al., 2015). Awe is increasingly recognized for its beneficial links to well-being, prosociality, and enhanced life satisfaction (Kitson et al., 2018). The experience of “small self” makes people less defensive, less ego-protective, and more receptive to new information and to seeking new experiences (Piff et al., 2015).

Awe has potential as a tool for mental health interventions. It has been described as a transformative emotion that can shift attention away from the self and open individuals to new perspectives (Chirico & Gaggioli, 2021), and it has been used to treat conditions such as depression and acute physical pain (Schony & Mischkowski, 2024). However, the use of awe in clinical or therapeutic contexts is still in its early stages, and more empirical research is needed to understand how it can be reliably elicited and applied.

How can Virtual Reality help to experience Awe?

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a promising tool to study awe in controlled experimental settings. VR enables the creation of immersive, interactive, and highly realistic environments that are well-suited to create awe-inducing scenes. Compared to traditional media, VR can enhance emotional engagement by offering a greater fidelity and a stronger sense of presence (Chirico et al., 2017). Moreover, VR enables researchers to create content that would be difficult or impossible to access in the real world.

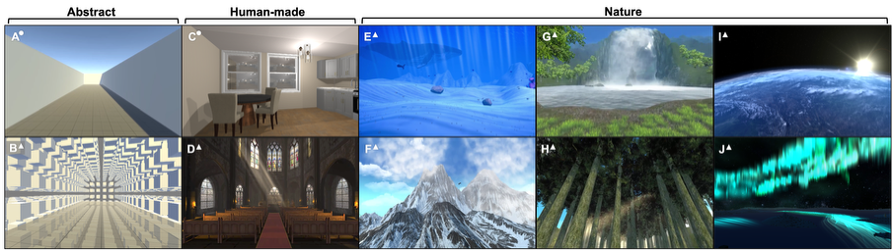

In a joint project with Bohn-Rhein-Sieg University of Applied Sciences, funded by the DAAD and JSPS, we created eight virtual environments that represent scenes designed to induce awe in virtual reality. The scenes are multimodal and include audio (Fig. 2).

In a study published in ISMAR last year (Steininger et al., 2025), these scenes were presented in VR to participants, and physiological signals were recorded along with self-reports. We collected data from nationals of Germany, Japan, and Jordan. Self-reported awe varied significantly across countries and scene types. In particular, a scene depicting outer space evoked the strongest sense of awe. Scenes that elicited high self-reported awe also induced a stronger sense of presence. However, we found no evidence that awe ratings are correlated with physiological responses.

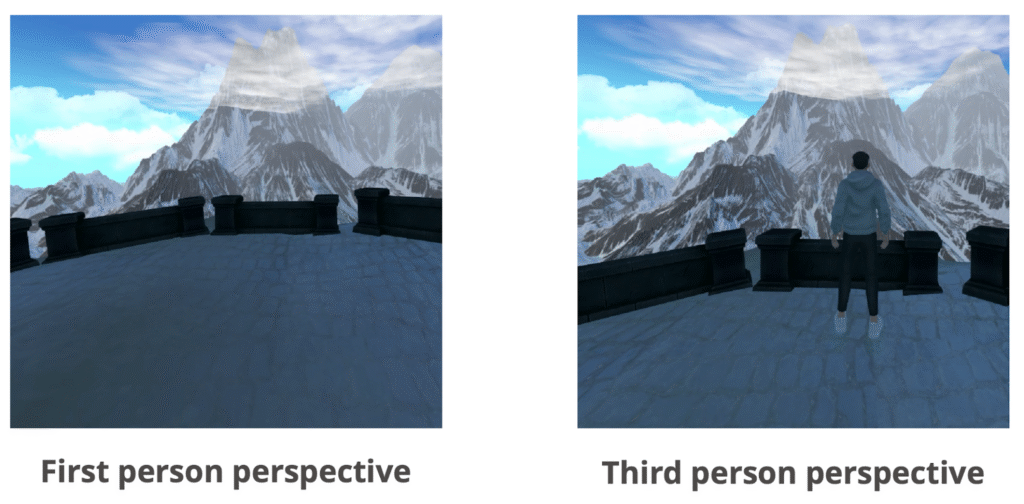

We also investigated which perspective would best induce Awe in VR (Fig. 3) (Otsubo et al., 2024). We compared first-person and third-person perspectives. Forty-two participants explored the VR scenes, with their physiological responses captured by electrocardiogram (ECG) and face tracking (FT). Subsequently, participants self-reported their experience of awe (AWE-S) and presence (IPQ) within VR. The results revealed that the first-person perspective induced stronger feelings of awe and presence than the third-person perspective.

In another study, we explored whether self-reported Awe could be predicted using skin conductance measurements (Steininger et al., 2024). Sixty-two participants took part in a study comparing an awe-eliciting space scene with a neutral scene. The space scene was found to be more awe-inspiring. A k-nearest neighbors algorithm confirmed the presence of high- and low-awe score clusters used to label the data. A Random Forest algorithm achieved 65% accuracy in predicting the self-reported low and high awe categories from continuous skin-conductance data.

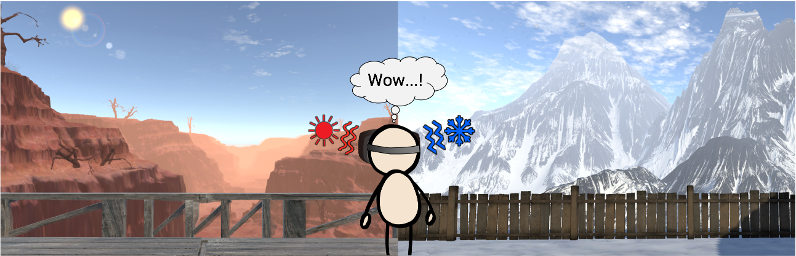

The previous study suggested that there is some relationship between embodied responses and Awe experience (Marquardt et al., 2025). Therefore, we tried the opposite direction. To modify the body state, i.e., the temperature of the body, to see if the awe experience changes. We developed a custom thermal feedback system integrated into a VR headset that delivers temperature sensations to the user’s face while viewing vast scenes of snow-covered mountains and desert canyons (Fig. 4). Our results show that thermal feedback significantly enhanced presence measures and influenced specific components of awe experiences, particularly those related to physical sensations.

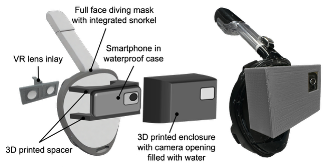

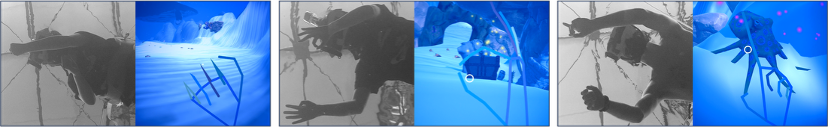

Finally, we iteratively developed a Head-Mounted Display to display our stimuli underwater (Fig.5) (Otsubo et al., 2023) and explored how to interact with the environment underwater using computer vision technology (Fig. 6) (Marquardt et al., 2024). An underwater virtual reality (UVR) system with gesture-based controls was developed to facilitate submerged navigation and interaction. The system uses a waterproof head-mounted display and camera-based gesture recognition, trained initially for above-water conditions, employing three gestures: grab for navigation, pinch for single interactions, and point for continuous interactions. In an experimental study, we tested gesture recognition both above and underwater, and evaluated participant interaction within an immersive underwater scene. Results showed that underwater conditions slightly affected gesture accuracy, but the system maintained high performance. Participants reported a strong sense of presence and found the gestures intuitive while highlighting the need for further refinement to address usability challenges.

Into the future of AWEsome experiences

Using the technology we developed, we are currently running a study to compare awe and immersive experiences above and below water. Pilot results suggest that experiencing our scenes underwater improves immersion and, therefore, Awe experiences.

We are also further exploring the possibility of hacking the body to improve our emotional experiences and regulation. All in all, I dream of being able to quantify user experiences and create experiences that we could not before. All thanks to technology.

About the author

Monica Perusquia-Hernandez received her BSc in electronic systems engineering (2009) from the Instituto Tecnologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Mexico; her MSc in human-technology interaction (2012) and the professional doctorate in engineering in user-system interaction (2014) from the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands. In 2018, she obtained her Ph.D. in Human Informatics from the University of Tsukuba, Japan. She is an Assistant Professor at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology. Her research interests include affective computing, biosignal processing, augmented human technology, and human-AI interaction.

References

Chirico, A., Cipresso, P., Yaden, D. B., Biassoni, F., Riva, G., & Gaggioli, A. (2017). Effectiveness of Immersive Videos in Inducing Awe: An Experimental Study. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01242-0

Chirico, A., & Gaggioli, A. (2021). The Potential Role of Awe for Depression: Reassembling the Puzzle. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617715

Joye, Y., & Bolderdijk, J. W. (2015). An exploratory study into the effects of extraordinary nature on emotions, mood, and prosociality. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01577

Keltner, D. (2023). Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life. Penguin.

Kitson, A., Prpa, M., & Riecke, B. E. (2018). Immersive Interactive Technologies for Positive Change: A Scoping Review and Design Considerations. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01354

Marquardt, A., Lehnort, M., Otsubo, H., Perusquia-Hernandez, M., Steininger, M., Dollack, F., Uchiyama, H., Kiyokawa, K., & Kruijff, E. (2024). Exploring Gesture Interaction in Underwater Virtual Reality. Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Symposium on Spatial User Interaction, SUI ’24, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3677386.3688890

Marquardt, A., Lehnort, M., Steininger, M., Kruijff, E., Kiyokawa, K., & Perusquia-Hernandez, M. (2025). Temperature Matters: Thermal Feedback for Awe Experiences in VR. 2025 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), 1352–1353. https://doi.org/10.1109/VRW66409.2025.00322

Maruskin, L. A., Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2012). The chills as a psychological construct: Content universe, factor structure, affective composition, elicitors, trait antecedents, and consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028117

Otsubo, H., Marquardt, A., Steininger, M., Lehnort, M., Dollack, F., Hirao, Y., Perusquia-Hernandez, M., Uchiyama, H., Kruijff, E., Riecke, B. E., & Kiyokawa, K. (2024). First-Person Perspective Induces Stronger Feelings of Awe and Presence Compared to Third-Person Perspective in Virtual Reality. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, ICMI ’24, 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1145/3678957.3685753

Otsubo, H., Schirm, J., Bachmann, D., Marquardt, A., Dollack, F., Perusquıa-Hernandez, M., Uchiyama, H., Kruijff, E., & Kiyokawa, K. (2023). Development of a Waterproof Virtual Reality Head-Mounted Display: An Iterative Design Approach.

Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018

Schony, M., & Mischkowski, D. (2024). The Role of Awe in Acute Physical Pain. The Journal of Pain, The 2024 USASP Annual Scientific Meeting, 25(4, Supplement), 64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2024.01.294

Steininger, M., Marquardt, A., Perusquia-Hernandez, M., Lehnort, M., Otsubo, H., Dollack, F., Kruijff, E., Krüger, B., Kiyokawa, K., & Riecke, B. E. (2025). The Awe-Some Spectrum: Self-Reported Awe Varies by Eliciting Scenery and Presence in Virtual Reality, and the User’s Nationality. 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), 1267–1277. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISMAR67309.2025.00132

Steininger, M., Perusquía-Hernández, M., Marquardt, A., Otsubo, H., Lehnort, M., Dollack, F., Kiyokawa, K., Kruijff, E., & Riecke, B. (2024). Using Skin Conductance to Predict Awe and Perceived Vastness in Virtual Reality. 2024 12th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops and Demos (ACIIW), 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACIIW63320.2024.00042